Growing up in Hamilton, Ill., Jerome Lee just wanted to play basketball. A three-sport athlete, his future was as open for him as an undefended layup. Then, between seventh and eighth grade, he broke his ankle. It was the first of several injuries. It was the first time he was prescribed painkillers.

Lee didn’t want to be in pain, and he didn’t want to become addicted. Like thousands of others across Illinois, one pill led to another, one prescription led to another and one addiction led to another.

That first prescription was for an opioid – a class of highly-effective pharmaceuticals such as oxycodone, codeine or hydrocodone. Like illegal opioids, these pain relievers are highly addictive – something providers who wrote prescriptions were not originally aware of. Only in the last few years has the addictive nature of the pills and the widespread abuse of opioids become apparent.

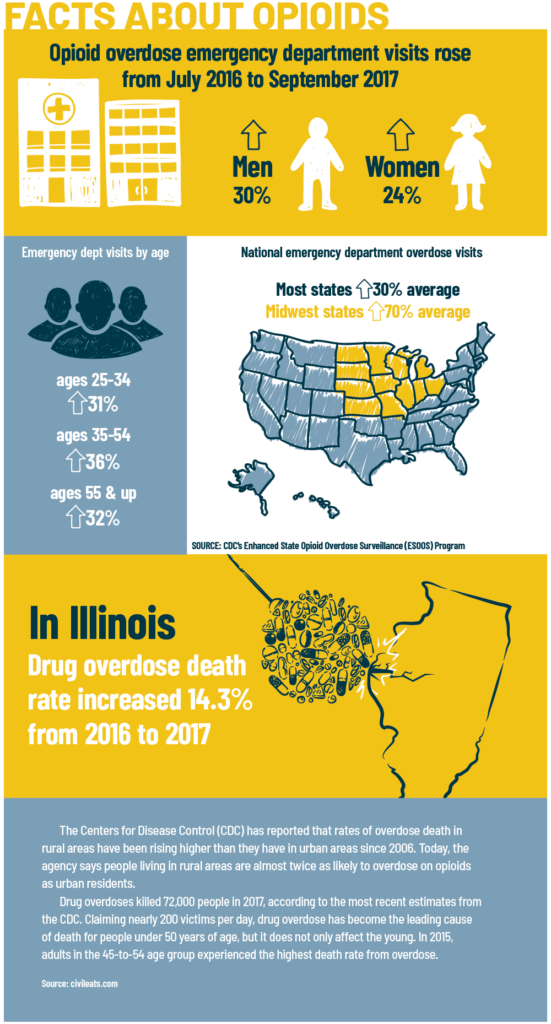

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, more than 47,000 Americans died in 2017 from opioid overdoses, including both prescribed medications and illegal opioids such as heroin. As many as 29 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain eventually misuse them.

“It used to be that if you were in pain, you were prescribed opioids,” explains Angie Bailey, system director of community health for Carbondale-based Southern Illinois Healthcare. “Later, we heard people were becoming addicted and it was all without the prescribers really understanding how addictive they were, and how quickly someone could become addicted.”

Opioids are still often prescribed for chronic pain or as a post-surgery pain killer because of their effectiveness. However, earlier this year the Center for Disease Control began recommending non-opioid approaches as the first step in pain relief.

“You just have to realize that primary care providers historically have been trained and encouraged to do all they can to manage people’s pain,” explains Angie Hampton, CEO of Egyptian Health Department which serves Gallatin, Saline, Wayne and White Counties.

Hampton says that desire to help their patients led to prescriptions for medicines that the physicians themselves, and definitely not the patients, knew could be addictive.

The truth is that as many as 12 percent of patients develop an opioid-use disorder.

“We hear stories all the time about how a young high school kid gets a sports injury and becomes addicted to their pain meds. A few years later, they’re addicted to other drugs, and it just spirals as an unintentional consequence,” Bailey explains.

Just as for Jerome Lee, taking pain pills every day for years led to more.

“I went from an opioid addiction to a methamphetamine addiction that ended up landing me in prison,” he says, adding that he tried meth for the first time not long after graduating from high school. “It went hand-in-hand with the pills.”

Even after the complete reconstruction of his ankle led doctors to tell Lee he no longer would need pain medicine, he continued to take the drugs.

“That’s when I realized I ‘needed’ the pills,” he recalls. “I used them for years to subdue my emotions and my feelings.”

Lee’s addiction was greater than any prescription he had, so he turned to illegally buying prescriptions from other people.

“It was easier for me to go out and buy them on the black market than it was to talk doctors into giving them to me,” he says.

Adding marijuana and alcohol to the mix, as well as meth, Lee’s life began a downward spiral. He lost his family due to divorce and had a $700 per day drug habit. To keep it up, he began dealing drugs. Only an arrest, two years in prison and a renewed faith helped him get clean.

Today, he works with the Hancock County Addiction Coalition bringing an addict’s perspective to programs and speaking to groups and students about the dangers of opioids and other drugs.

“When I got out, the first thing I did was go to the sheriff’s office and ask, ‘Do you do anything with DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Program) or anything? I want to help somewhere.’ The sheriff sent me to a meeting of the coalition.”

Groups like the coalition are working across the state to battle the opioid crisis, especially in rural areas.

“I don’t know if opioid abuse is more prevalent in rural areas or not, but I can tell you that we know about it more often because in these areas with smaller populations we know everybody, and everybody knows everybody’s business,” adds Kristin Parks, clinic practice manager for Ferrell Hospital in Eldorado.

She says the lack of population may make area residents more prone to abusing opioids.

“We have to realize that we have very few [medical services] for our young and elderly,” she begins to explain. “If you fall and break your back and are in metropolitan Chicago, you could go two blocks one way to see your physical therapist and you might be able to go two blocks the other way for the occupational therapist. You might not even have to leave the building to see a neurosurgeon. Here, our patients travel no less than one hour in any direction to be seen at a larger facility. When you have no resources to offer and the limited finances they deal with – some of them don’t even have a car – trying to get from here to a larger hospital is just impossible. So they take to medicating themselves however they can.”

A snowball

The problems of the opioid crisis reach far beyond individual patients and their families. Opioids are putting a burden on health care systems, social services and law enforcement.

“I’ve really seen an increase in opioids in the last five years,” says Jasper County Sheriff Brandon Francis. “We don’t have that many resources, but we spend a considerable amount of time dealing with all kinds of issues that stem from opioids.”

Francis says his department sees opioids as a part of many other problems.

“We are dealing not just with opioids but with a lot of other things that come with it,” he says. “It is very common that people who are on opioids are committing other crimes. It’s different in every case, but it can lead to burglaries, domestic situations or cases where we have to call in the Department of Child and Family Services. It’s like a snowball.”

Woodford County Deputy Jail Superintendent Dennis Wertz says another challenge for law enforcement is the needs of incarcerated addicts. “As far as corrections goes, we get a lot of people here [in the county jail] who are going through withdrawals and we have to start them on a medical protocol to deal with the withdrawals,” he says.

He adds that patrol officers must carry naloxone, a treatment for opioid overdose, and know how to administer the drug.

Opioid abuse reaches across the community says Ánna Jurich, executive director with Gateway Foundation, a drug and alcohol abuse treatment organization with 14 locations throughout Illinois.

“There is a huge impact on our communities, and to society in general, as far as the cost of people being unemployed, cost for the medical concerns, problems with needles that are potentially sabotaging our playgrounds, and the families that are impacted,” she says.

Strain on rural communities

Perhaps nowhere is the burden of opioid abuse felt as strongly as it is in health care settings.

Bailey says a statewide prescription monitoring program is now in place so that physicians and other medical personnel can make certain that patients are not receiving prescriptions for opioids from multiple providers. The effort works through a cooperative effort of health care providers and pharmacists.

She says her health care system has also developed a “warm hand-off” program where patients in the emergency department with a substance abuse problem can immediately be referred to a counselor from a drug treatment facility.

Sometimes finding and making referrals to treatment options is difficult.

“The biggest challenge we have is that we don’t have enough detox facilities,” explains Ada Bair, CEO of Hancock County UnityPoint Health – Memorial Hospital in Carthage. “One of the biggest strains on our emergency department is that no matter what the substance is, we have to find a place that will accept them and transfer. Because we are a small hospital, we are not equipped to keep them to detox and help them start recovery.”

“You have to be able to find a place for them to go for rehab and then make sure your community has support for when they come back. That’s one of the biggest pitfalls,” she adds. “If you don’t have that, they recycle right back into the addictive mode. Recovery is not a short-term thing.”

Health care leaders add that medical providers are taking a leading role in finding alternatives to prescribing opioids. Many are turning to physical therapy or other treatment options instead of pain killers. New surgical methods such as robotic-assisted surgery requires smaller incisions, requiring less treatment of pain.

“Our emergency department providers are taking a very strong stance. They are not prescribing medications unless there’s something that really necessitates it and then only for a day or two until the patient can get back to their primary care provider,” Bair adds.

She says patients who are on prescription medications are required to sign agreements that they will use the medicines as prescribed and are willing to be subject to random drug screenings to make sure they are using

it themselves.

“We want to see that the medication is truly in their system,” she explains. “We don’t want to see a clean drug screen because that means they might be selling it.”

Once patients no longer need medications, many law enforcement offices, health departments and medical facilities offer drug take-back events or drop boxes where opioids can be disposed of safely.

“We have worked hard to educate the public that you can’t leave old pain medication in your medicine cabinet,” adds Parks. “We’re collecting all of these prescriptions so they’re not sitting out there for anybody with an addiction problem to get their hands on. A lot of it is just community education.”

Community outreach, cooperation and education seems to be the key to combating the opioid crisis.

“We are getting to the point where we can talk about opioid and other substance addictions the same way we can talk about diabetes or high blood pressure,” says Parks. “It’s not the elephant in the room anymore.”

That means former addicts like Jerome Lee will continue to tell their stories.

“I give my testimony and tell everyone that we can beat this,” Lee says. “I think we’re headed in the right direction.”

“I am very proud of what our rural communities are already doing to combat opioids and what they’re attempting to do to educate and support them,” says Bair. “We’re going to get out in front of this and prevent it in the future.”

If you or someone you know is battling an opioid or other substance abuse addiction, help is available by calling the Illinois Helpline at 833-2FINDHELP.