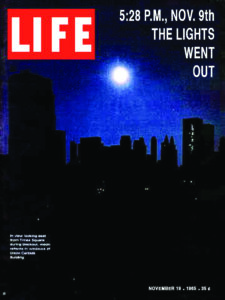

“Where were you when the lights went out?” became a catch phrase more than 50 years ago, when The Great Northeast Blackout occurred. It was joked about in popular TV shows of the day like “Green Acres” and “Bewitched.” But to utilities and policy makers on both sides of the Great Lakes, the blackout was no laughing matter. It exposed issues in the humongous North American electrical highway called “the grid,” the largest machine mankind ever built, that interconnects power generators, power lines and the electric consumers.

“Where were you when the lights went out?” became a catch phrase more than 50 years ago, when The Great Northeast Blackout occurred. It was joked about in popular TV shows of the day like “Green Acres” and “Bewitched.” But to utilities and policy makers on both sides of the Great Lakes, the blackout was no laughing matter. It exposed issues in the humongous North American electrical highway called “the grid,” the largest machine mankind ever built, that interconnects power generators, power lines and the electric consumers.

“That was the first blackout of that scale in the United States and really got the attention of our government,” said Barry Lawson, Associate Director of Power Delivery and Reliability with the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association.

Soon after, Congress demanded improvements. Utilities that generated and transmitted electricity came together to create a voluntary organization — the National Electric Reliability Council (NERC) — to establish standards and policies and provide peer oversight. “It put into place a lot of practices and policies that the industry agreed to do,” Lawson said.

Since then, innovations in technology have allowed for better gathering of data and monitoring of the flow of power across the grid. But at the same time, changing laws and regulations fundamentally shifted the way the grid and utilities operate. A whole new set of challenges has arisen — affecting the largest power producers down to the smallest distribution cooperatives.

A patchwork of design

North America’s electric grid is truly a marvel of engineering, but it wasn’t initially designed to be an interconnected grid. It was created as needed — over the course of 100 years — one section at a time.

The traditional utility model was vertically integrated. In a given service territory, one utility owned and operated the power plants and the transmission and distribution power lines to meet the needs of the consumers in that territory.

Over time, utilities connected with neighboring utilities for mutual benefits — like backup power when needed during planned or unplanned outages. The networks grew. Today’s grid includes 3,360 utilities and other entities operating 7,677 power plants sending energy across 450,000 miles of transmission lines and 5.5 million miles of distribution.

There are actually three power grids in the 48 contiguous states: the Eastern Interconnection (generally for states east of the Rocky Mountains); the Western Interconnection (for states from the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean); and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (which covers approximately 85 percent of Texas). The three grids operate as islands, independent of each other for the most part.

Girding of the grid

After NERC came along in 1968, overall reliability improved for 30 years. “It worked well in the vertically-integrated industry-owned transmission model,” said Lawson.

Congress tossed the monkey wrench of unintended consequences into the already complicated grid works in 1992 when it deregulated the generation of electricity. The “vertical” began to break down as competitive independent generators, with no transmission operations or obligations to serve a given territory of consumers, entered the wholesale marketplace. Owners of existing transmission lines were required by law to allow open access to the network.

By the late 1990s, with all comers allowed to enter the fray, voluntary compliance with NERC standards and policies became inconsistent. New reliability problems began showing with outages in the Western grid. Lawmakers and utility industry folks talked about establishing additional oversight.

“It was not clear if this voluntary regulatory group using peer pressure would be able to continue to ensure the high level of grid reliability that the utility industry provided,” Lawson said.

That answer became clearer Aug. 14, 2003.

During that hot afternoon when power use was high, a series of malfunctions, mishaps and mistakes escalated into the worst blackout in North American history.

It started when heavily loaded transmission lines sagged into overgrown trees in Northern Ohio, causing those lines to fail. Alarms malfunctioned, and the severity of the situation went unrecognized until it was too late. Just as in 1965, a blackout cascaded across the Northeast. Some 300 transmission lines failed. Well over 50 million people were affected throughout Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Vermont. The outage also spread into Ontario, Canada.

An estimated $10 billion economic loss was attributed to the blackout. While the vast majority of consumers had electricity restored within 48 hours, some parts of the United States did not have power for four days.

The 2003 blackout pushed reforms into “hyper-speed mode,” Lawson said. “Congress finally said, ‘We need something with teeth that’s mandatory and enforceable.’”

The ensuing Energy Policy Act of 2005 gave the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission authority over reliability. FERC chose NERC as the oversight organization, giving it new powers. In 2007, NERC’s 83 Reliability Standards were approved by FERC as the first set of legally enforceable standards for the U.S. bulk power system.

Coming down the lines

Even though electricity is at our fingertips almost 100 percent of the time, getting it to our homes and workplaces from where it’s generated is a challenging process. Because large amounts of energy cannot be stored, electricity must be produced as it is used.

The grid must respond quickly to shifting demand and continuously generate and route electricity to where it’s needed the most. But significant changes and challenges are coming down the line. Issues affecting the grid include:

- Age. Parts of the electrical transmission facilities in the United States are many decades old. Given the age, some existing lines have to be replaced or upgraded and new lines may need to be constructed to maintain the electrical system’s overall reliability.

- New technology. Upgrades in technology now let consumers connect their own home-generated electricity to the grid — using solar panels or wind generators. Investments are being made in smart grid digital technology to more efficiently manage energy resources. A smarter grid will be needed to integrate intermittent renewable energy like solar and wind.

- Cost. The smart grid and better reliability will not be free. According to a study done by the Electric Power Research Institute, creating a smart grid could cost up to $476 billion over the next 20 years. But EPRI noted the country is likely to recoup those costs — and then some. The report said the smart grid could provide up to $2 trillion in benefits over a 20-year period, such as power reliability, integration of renewable energy, stronger cybersecurity and better management of electricity demand.

- Renewables. Federal climate change policy will rely on boosting energy efficiency and developing more sources of renewable energy. Both will impact the grid. Renewable energy resources will likely require construction of entirely new transmission lines. Wind, solar, geothermal, and other forms of renewable energy typically share a common problem. The areas where the power can be generated best are not near population centers. New transmission lines must be built to move the power.

- Security. The grid may be vulnerable to both physical and cyber attacks that could cause a blackouts.

Are these new challenges capable of creating a cascading blackout on the scale of the one in 2003 or 1965? “You can’t say it could never happen again. There are still things we haven’t planned for or have protections for, or are too costly to plan for,” Lawson said.

This article and accompanying sidebars were compiled, written in most part, and edited by Richard G. Biever, senior editor of Electric Consumer. Contributions were edited from articles by the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Other sources of information included Wikipedia, the American Public Power Association and NERC.