Creating a new state is no easy task, but a group of concerned citizens in west-central Illinois attempted to do just that more than 50 years ago. … Well, sort of.

In what could be considered a grab for attention, Forgottonia became a movement to raise awareness of a 16-county region in the bulge of western Illinois and its lack of transportation infrastructure projects in the area. In the 1960s, when the interstate road system was formed, a large chunk of western Illinois was bypassed. With lagging economic growth and residents moving away, a small group decided to take matters into its own hands.

The publicity stunt itself was a symbolic gesture of secession, declaring war and then immediately surrendering.

“It was a bit of a satire … tongue-in-cheek,” says Sue Scott, director of Western Illinois Museum in Macomb. “It was a group of people trying to give voice to the concerns that they had, in a way they thought would reach a broader audience.”

That key group of people included Coca-Cola bottler Frank “Pappy” Horn, his son Jack Horn (who is said to have coined the name Forgottonia), Macomb Chamber of Commerce board member John Armstrong and Neal Gamm, the face of the movement.

“They all had their interest,” Scott explains, indicating that the Horns likely sought better roads to distribute soda and Armstrong to boost local businesses. “And then Gamm, I think he was just a bit of a showman … a rebel.”

![Neal Gamm, governor of Forgottonia, is depicted in many tongue-in-cheek photographs promoting the movement. All historical photos

Creating a new state is no easy task, but a group of concerned citizens in west-central Illinois attempted to do just that more than 50 years ago. … Well, sort of.

In what could be considered a grab for attention, Forgottonia became a movement to raise awareness of a 16-county region in the bulge of western Illinois and its lack of transportation infrastructure projects in the area. In the 1960s, when the interstate road system was formed, a large chunk of western Illinois was bypassed. With lagging economic growth and residents moving away, a small group decided to take matters into its own hands.

The publicity stunt itself was a symbolic gesture of secession, declaring war and then immediately surrendering.

“It was a bit of a satire … tongue-in-cheek,” says Sue Scott, director of Western Illinois Museum in Macomb. “It was a group of people trying to give voice to the concerns that they had, in a way they thought would reach a broader audience.”

That key group of people included Coca-Cola bottler Frank “Pappy” Horn, his son Jack Horn (who is said to have coined the name Forgottonia), Macomb Chamber of Commerce board member John Armstrong and Neal Gamm, the face of the movement.

“They all had their interest,” Scott explains, indicating that the Horns likely sought better roads to distribute soda and Armstrong to boost local businesses. “And then Gamm, I think he was just a bit of a showman … a rebel.”

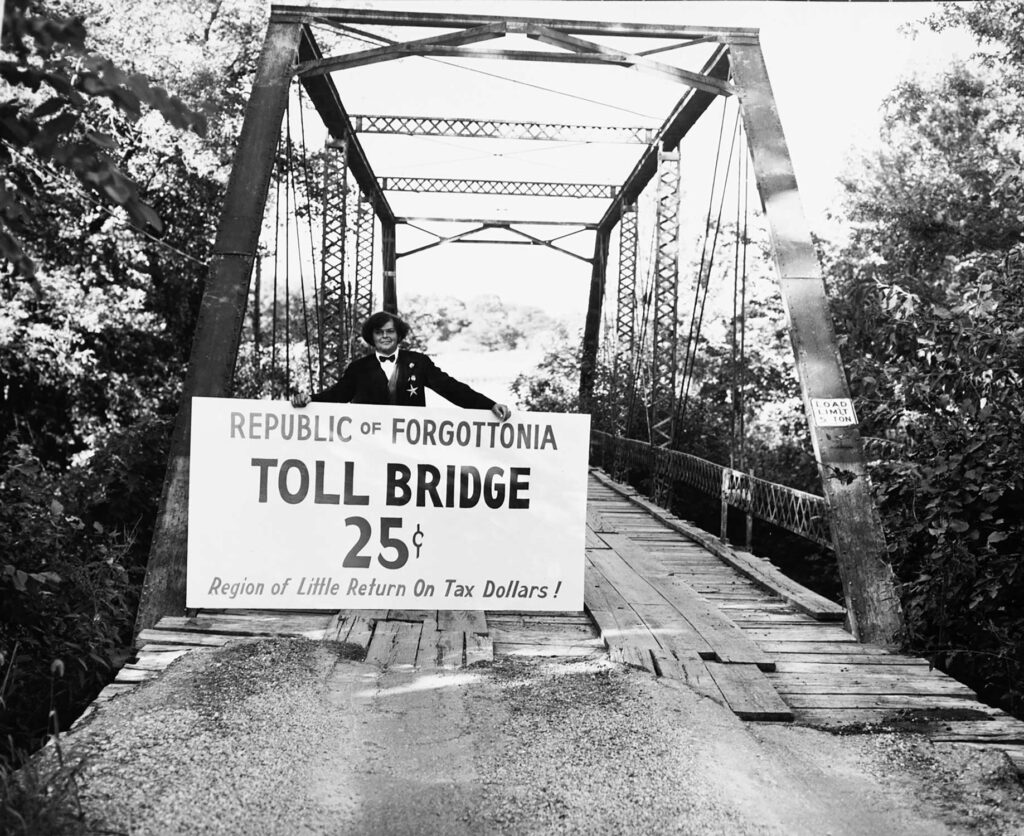

Gamm, who was a fine arts and theater student at Western Illinois University, was declared the governor of the symbolic state. He is depicted in photo ops wearing a frock coat and a bowtie charging a 25-cent toll at an old bridge, checking someone’s travel visa upon entering the “independent republic,” and standing in Fandon, Forgottonia’s capitol, an unincorporated community in McDonough County located south of Macomb.

“If you blink, you’ll miss it, literally,” says Jock Hedblade, executive director of the Macomb Area Convention and Visitors Bureau, about driving through Fandon. “It’s that small. But it was a big deal.”

The Forgottonia movement put Fandon on the map, but not because of booming industry, scenery or travel. It was because of publicity shots of Gamm around the community, standing in front of abandoned or worn-out buildings labeled as the “Governor’s Mansion” or “Capitol Building,” for example — most of which are gone today.

Of course, Fandon being Forgottonia’s capital was part of the joke, as was the state flower being the forget-me-not, the state bird being the albatross, which also means, “something that causes deep concern,” and the state flag being the white flag of surrender.

The movement gained national media attention, and while many of the locals were in on the joke, others were unhappy and didn’t find it funny. Some of those negative opinions still exist today.

“Part of the community didn’t like it at all,” Scott says. “A lot of people found it offensive. They found [Gamm] a caricature of what people in rural America look like. I think some people felt they were being made fun of. … People were saying, ‘Hey, we don’t look like that. We don’t talk like that.’”

Hedblade agrees. “There is a faction of the community that has a negative connotation about Forgottonia,” he says. “Some take that name at face value and then take umbrage because of it. What they’re not seeing is the story behind it … the fact that the reason why this whole thing came about was because this part of the state had no infrastructure.”

Hedblade grew up in Macomb and remembers the start of Forgottonia as a young teenager. He believes any successes from the Forgottonia movement stem from it being humor-based with a serious message behind it.

“That message embarrassed the state, and it kind of forced them into taking care of this area,” Hedblade says. “The bottom line is, whatever you thought of it, it had a positive impact on this area. … We want to show that there are so many layers to the story and that it had a positive impact that helped transform this area.”

The movement may have produced some change. The interstate system didn’t originally include west-central Illinois. However, the Central Illinois Expressway, now known as Interstate 72 and Interstate 172, began development in the late ’70s and now connects Quincy with Springfield and Champaign.

However, Scott isn’t convinced that the Forgottonia movement achieved the change it intended to, but “in some ways, it did galvanize people at that time to try to do something a bit more within the state government system.”

She also believes the meaning of Forgottonia has changed over time. “I think it’s come to represent something different,” she says.

For the Western Illinois Museum, it’s about collecting oral histories. Thanks to a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, the museum holds a summer program with high school students to collect local oral histories.

She explains that while Forgottonia is certainly part of local history, this program isn’t all about that specific history. More accurately, the program focuses on the idea of the forgotten story or narrative. Using primary sources, these students are gaining a better understanding of local histories and the importance of sharing them.

“[Forgottonia] seems to be a catchy way for young people to enter into thinking about [their community],” Scott says. “What makes it Forgottonia? What is being forgotten? What can be done to make sure that it’s not forgotten? We’re trying to teach young people that they have a role in collecting their local history, preserving it and deciding which part of that history gets told.”

Something similar can be said about the Macomb Area Convention and Visitors Bureau, which has dubbed the area as Unforgettable Forgottonia.

Hedblade returned to Macomb six years ago after many years of working in media. Heading up the visitor’s bureau, he knew the area needed a new brand. With the help of a marketing agency, Unforgettable Forgottonia was born.

“We needed something different, and [Forgottonia] was just hanging there. … Not many people know what it means, but it makes you curious. … It sounds whimsical, it sounds different, it sets us apart, and it’s ours. [Forgottonia] was created here,” Hedblade says. “And it’s worked, particularly outside of this community.”

He says that since the rebranding, tourism has grown exponentially. He credits much of that to the spirit of Forgottonia. The idea is to take pieces of obscure and nearly forgotten history and create a destination out of them.

For example, Abraham Lincoln made a stop in Macomb during his tour of the state while debating Stephen Douglas for senate. During his stay, Lincoln spoke with an audience at the Macomb courthouse. This moment in history was honored with the Living Lincoln Topiary Monument, which was unveiled outside Macomb’s City Hall in August 2020. It is a bust of Lincoln, his beard alive with colorful plants. The U.S. National Park Service later named Macomb as an official Abraham Lincoln National Heritage Area in June 2021.

“Sometimes, you’ve got to get far away from something to be able to look back and see what the real importance of it was,” Hedblade says. “I think if this does nothing else, I would be happy if it changes people’s attitudes about what this story is … if it puts it in a better light, and that people can understand how important it was and still is, and why we need to embrace that history.”

In 2011, “How the States Got Their Shapes” host Brian Unger interviewed Neal Gamm in Fandon for the second episode of the series, “The Great Plains, Trains and Automobiles.” In the episode, Gamm says, “It all started as a publicity stunt. We were just forgotten by the state and federal government, so we just ought to secede.” Gamm passed away in November 2012 at age 65.

More than a decade later, on Sept. 9, 2023, Fandon saw a flurry of excitement as people gathered to observe the 50th anniversary of Forgottonia and honor the satirical governor. “We probably tripled the population that day,” Hedblade laughs. During the event, the thoroughfare through Fandon was officially declared as Gov. Neal Gamm’s Forgottonia Veterans Freeway.

“Knowing that [Gamm] was an actor and performer at heart, I think that he would have been very proud of what happened here,” Hedblade speculates. “I can’t imagine that he wouldn’t have wanted to participate fully in [the anniversary event]. And not just for the limelight of it, but just the knowledge and the recognition that what he did — that started as a joke, really — had a lasting impact and is now only growing stronger than it ever has.”

By Colten Bradford

“It was a bit of a satire … tongue-in-cheek. It was a group of people trying to give voice to the concerns that they had, in a way they thought would reach a broader audience.”

- Sue Scott, Western Illinois Museum

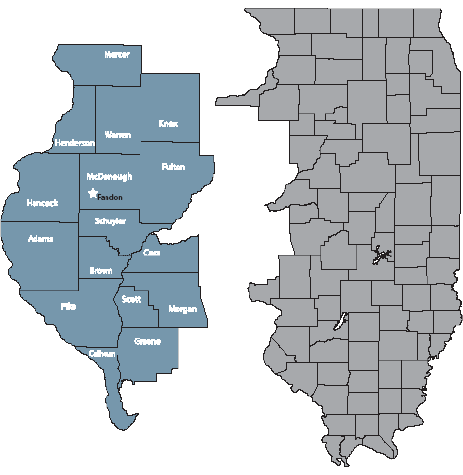

Forgottonia consists of 16 counties in western Illinois. The capital of Fandon is located south of Macomb in McDonough County.

Neal Gamm, governor of Forgottonia, is depicted in many tongue-in-cheek photographs promoting the movement. Photos courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Western Illinois University Libraries](https://icl.coop/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Forgottonia_800_8079.jpg)

Gamm, who was a fine arts and theater student at Western Illinois University, was declared the governor of the symbolic state. He is depicted in photo ops wearing a frock coat and a bowtie charging a 25-cent toll at an old bridge, checking someone’s travel visa upon entering the “independent republic,” and standing in Fandon, Forgottonia’s capitol, an unincorporated community in McDonough County located south of Macomb.

“If you blink, you’ll miss it, literally,” says Jock Hedblade, executive director of the Macomb Area Convention and Visitors Bureau, about driving through Fandon. “It’s that small. But it was a big deal.”

The Forgottonia movement put Fandon on the map, but not because of booming industry, scenery or travel. It was because of publicity shots of Gamm around the community, standing in front of abandoned or worn-out buildings labeled as the “Governor’s Mansion” or “Capitol Building,” for example — most of which are gone today.

Of course, Fandon being Forgottonia’s capital was part of the joke, as was the state flower being the forget-me-not, the state bird being the albatross, which also means, “something that causes deep concern,” and the state flag being the white flag of surrender.

The movement gained national media attention, and while many of the locals were in on the joke, others were unhappy and didn’t find it funny. Some of those negative opinions still exist today.

“Part of the community didn’t like it at all,” Scott says. “A lot of people found it offensive. They found [Gamm] a caricature of what people in rural America look like. I think some people felt they were being made fun of. … People were saying, ‘Hey, we don’t look like that. We don’t talk like that.’”

Hedblade agrees. “There is a faction of the community that has a negative connotation about Forgottonia,” he says. “Some take that name at face value and then take umbrage because of it. What they’re not seeing is the story behind it … the fact that the reason why this whole thing came about was because this part of the state had no infrastructure.”

Hedblade grew up in Macomb and remembers the start of Forgottonia as a young teenager. He believes any successes from the Forgottonia movement stem from it being humor-based with a serious message behind it.

“That message embarrassed the state, and it kind of forced them into taking care of this area,” Hedblade says. “The bottom line is, whatever you thought of it, it had a positive impact on this area. … We want to show that there are so many layers to the story and that it had a positive impact that helped transform this area.”

The movement may have produced some change. The interstate system didn’t originally include west-central Illinois. However, the Central Illinois Expressway, now known as Interstate 72 and Interstate 172, began development in the late ’70s and now connects Quincy with Springfield and Champaign.

However, Scott isn’t convinced that the Forgottonia movement achieved the change it intended to, but “in some ways, it did galvanize people at that time to try to do something a bit more within the state government system.”

She also believes the meaning of Forgottonia has changed over time. “I think it’s come to represent something different,” she says.

For the Western Illinois Museum, it’s about collecting oral histories. Thanks to a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, the museum holds a summer program with high school students to collect local oral histories.

She explains that while Forgottonia is certainly part of local history, this program isn’t all about that specific history. More accurately, the program focuses on the idea of the forgotten story or narrative. Using primary sources, these students are gaining a better understanding of local histories and the importance of sharing them.

“[Forgottonia] seems to be a catchy way for young people to enter into thinking about [their community],” Scott says. “What makes it Forgottonia? What is being forgotten? What can be done to make sure that it’s not forgotten? We’re trying to teach young people that they have a role in collecting their local history, preserving it and deciding which part of that history gets told.”

Something similar can be said about the Macomb Area Convention and Visitors Bureau, which has dubbed the area as Unforgettable Forgottonia.

Hedblade returned to Macomb six years ago after many years of working in media. Heading up the visitor’s bureau, he knew the area needed a new brand. With the help of a marketing agency, Unforgettable Forgottonia was born.

“We needed something different, and [Forgottonia] was just hanging there. … Not many people know what it means, but it makes you curious. … It sounds whimsical, it sounds different, it sets us apart, and it’s ours. [Forgottonia] was created here,” Hedblade says. “And it’s worked, particularly outside of this community.”

He says that since the rebranding, tourism has grown exponentially. He credits much of that to the spirit of Forgottonia. The idea is to take pieces of obscure and nearly forgotten history and create a destination out of them.

For example, Abraham Lincoln made a stop in Macomb during his tour of the state while debating Stephen Douglas for senate. During his stay, Lincoln spoke with an audience at the Macomb courthouse. This moment in history was honored with the Living Lincoln Topiary Monument, which was unveiled outside Macomb’s City Hall in August 2020. It is a bust of Lincoln, his beard alive with colorful plants. The U.S. National Park Service later named Macomb as an official Abraham Lincoln National Heritage Area in June 2021.

“Sometimes, you’ve got to get far away from something to be able to look back and see what the real importance of it was,” Hedblade says. “I think if this does nothing else, I would be happy if it changes people’s attitudes about what this story is … if it puts it in a better light, and that people can understand how important it was and still is, and why we need to embrace that history.”

In 2011, “How the States Got Their Shapes” host Brian Unger interviewed Neal Gamm in Fandon for the second episode of the series, “The Great Plains, Trains and Automobiles.” In the episode, Gamm says, “It all started as a publicity stunt. We were just forgotten by the state and federal government, so we just ought to secede.” Gamm passed away in November 2012 at age 65.

More than a decade later, on Sept. 9, 2023, Fandon saw a flurry of excitement as people gathered to observe the 50th anniversary of Forgottonia and honor the satirical governor. “We probably tripled the population that day,” Hedblade laughs. During the event, the thoroughfare through Fandon was officially declared as Gov. Neal Gamm’s Forgottonia Veterans Freeway.

“Knowing that [Gamm] was an actor and performer at heart, I think that he would have been very proud of what happened here,” Hedblade speculates. “I can’t imagine that he wouldn’t have wanted to participate fully in [the anniversary event]. And not just for the limelight of it, but just the knowledge and the recognition that what he did — that started as a joke, really — had a lasting impact and is now only growing stronger than it ever has.”