Driving through the countryside between Ipava, Table Grove and Bernadotte, Ill. all you see is farmland and ghosts of what it used to be. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 1,100 people reside in these three communities combined, but during World War II, this area was a hub of activity with the cracking sounds of gunfire, planes flying overhead and incarcerated prisoners of war. This was Camp Ellis.

“There was a city here,” Marion Cornelius says, curator of the Easley Pioneer Museum in Ipava, which is home to a Camp Ellis exhibit. “It’s hard to believe when you drive out there how many people were there during the heyday of Camp Ellis.”

The camp opened in 1943 as a WWII Army Service Forces Unit Training Center. According to Cornelius, there were several Army camps in the U.S. that trained people to fight, but there wasn’t a place to train support personnel. Then on Dec. 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred, and that need came to the forefront.

The location between the three small communities was chosen because of the low population, flat land, wooded area and proximity to Spoon River. In 1942, the U.S. Army began purchasing land in the area totaling 17,500 acres. The people already living there were essentially evicted.

“They knocked on your door and had a paper with the legal description of your land telling you that your land had been condemned for public purposes,” Cornelius says. Those who received this letter had 30 days to vacate and were informed of the amount of money they were being paid for their land.

“You could take your barn, you could take your house, you could take your cows, all they wanted was the dirt. Everything else must go,” Cornelius explains. “In 30 days, anything still there would be demolished.” Residents were forced to sell their land but didn’t know when they would get their money. “You had to go look to buy another farm and you had no money to buy it with. It was quite a problem.”

Although many families were unhappy for being displaced from their homes, Camp Ellis had a positive impact on the local economy. “This area hadn’t really gotten out of the depression yet,” Cornelius explains. “Jobs were hard to find… This was the best thing that ever happened to many people because they had jobs where they didn’t have them before.”

Many local citizens worked at the camp fulltime. They worked construction as it was being built, worked operations, in the hospital, in the firehouses and more. Cornelius says he frequently gets visitors who says they had a relative who worked at Camp Ellis. He even met someone who traveled from Missouri to work.

Camp Ellis was built quickly. A railway from Table Grove was the first item on the list built because building supplies needed to arrive by train. Cornelius says during the construction of the camp, an average of 100 boxcar loads of material were delivered to the camp each day.

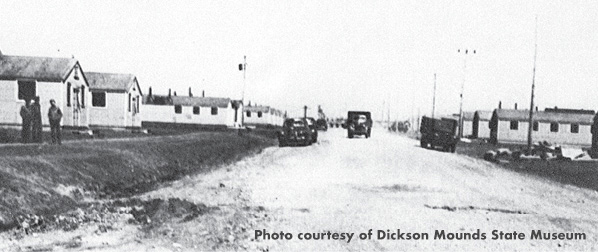

From there, a total of 2,200 buildings, a hospital, airport, and water and sewage systems were built. The camp was dedicated on July 4, 1943 but was already up and running earlier that year.

“Camp Ellis was not there to train people to fight, but to train support people,” Cornelius explains. “However, people were trained to defend themselves.” Those who came to Camp Ellis did get basic training and learned how to shoot and throw hand grenades. “You learned how to defend yourself in case you needed to, but that wasn’t going to be your job.”

For the most part, medical personnel, quartermasters and engineers were trained at the camp.

The hospital was a state-of-the-art facility at the time covering 160 acres. “The hospital was arguably the largest hospital in the country at the time,” Cornelius says. “They were innovators at this hospital.”

Camp Ellis was home to an early prototype of what came to be known as the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital or MASH. “People at the hospital decided that if they could train a complete surgical unit… and fly them somewhere to set up a tent hospital in 24 hours, they could save a lot of lives,” he explains. Therefore, the airport was built.

The hospital’s rehabilitation program housed injured veterans, and Camp Ellis was a center for training dentists.

“A large part of the hospital was dental,” Cornelius says. Men were being drafted for the war and were trained to shoot. “It’s difficult to shoot a rifle straight with a toothache. [A lot of draftees] were coming from rural areas, and dental facilities in rural areas were almost nonexistent. You had to get rid of that toothache before teaching the recruit how to shoot.”

The quartermasters, who Cornelius called cooks and bottle washers, were trained to support the people who were fighting by taking care of their needs. Cornelius shared an example of the quartermaster baking school where the men would dig a fox hole, mix bread dough and bake the bread in a makeshift oven dug into the earth.

Engineers were needed in the war to build bridges, roads and put up communications. Cornelius estimates 300 bridges were built across nearby Spoon River.

“They’d build a bridge across and move a bunch of men. Then tear that bridge down and go up the river again,” he explains. They were practicing building them because of the bridges being blown up in Europe. “They had to know how to build bridges fast.”

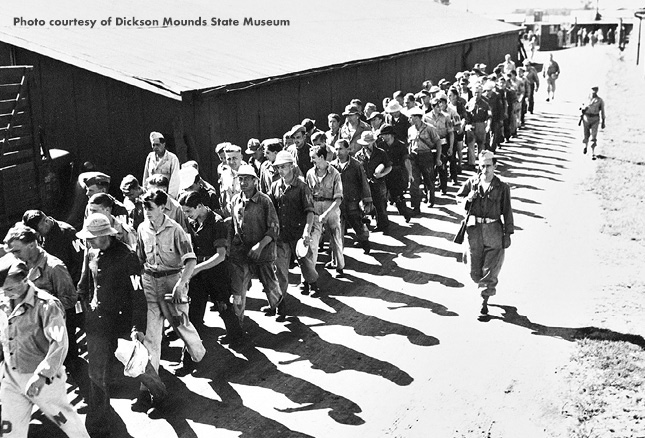

While mainly used for training, Camp Ellis also housed prisoners of war (POWs). Cornelius says the camp wasn’t originally intended to hold POWs. It was more of an afterthought, and extra buildings were built to house the prisoners.

“Camp Ellis held more POWs than any other place in Illinois,” Cornelius notes. “There were nine locations in Illinois that housed them.” He estimates there were close to 7,500 POWs, mostly German, that came to Camp Ellis during the war, but there weren’t more than 5,000 there at one time.

“All those POWs knew how our guys were being treated over there, and it wasn’t good,” Cornelius explains. “They expected to get the same treatment, but that wasn’t true… They lived a life they weren’t used to. They ended up in brand-new buildings in beds that had clean sheets and wool blankets to stay warm in the winter, and all the buildings had heat.”

The holding for POWs was minimum security. After a screening process, the hardcore Nazis were sent to other camps. Cornelius says the POWs at Camp Ellis were the ordinary soldiers.

While there, the POWs worked. If they were good at mechanics, they worked in the motor pool. Others were driven to local farms to work. After a bad ice storm, they cleaned up trees, and two different years they sandbagged the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers because of flooding.

“They were pretty much free, and some didn’t even have a guard. They had a job to do and then return,” Cornelius says. “They knew they were treated well and were happy to work.” The POWs were even paid.

“They would create articles out of metal or wood and would barter with the locals and trade them for candy and cigarettes,” he says. The museum now has several of these items including two of the Three Wise Men that were hand carved out of wood, a wooden cigarette box, an ornate wooden jewelry box and metal rings.

There was only one successful escape, and that’s because of the POW’s English. “He really didn’t escape,” Cornelius says. “He just picked up the fence, walked out, hitched a ride to Peoria and got a train to Chicago… He didn’t get discovered until 1953, and by that time, he had a family.” Like the other POWs, he was sent back to Germany, but later returned to Chicago.

For the most part, Cornelius says they didn’t want to go home. When they left, it took several years to get home. Once they arrived in Great Britain or France by boat, they stayed for several years, forced to help rebuild after the war, and when they finally got home, there wasn’t much home to go to. “Things were bad in Germany,” he explains. “Germany had to rebuild just as much as any of the other countries. It wasn’t a good outlook.”

The camp stayed active for three years until VE Day in 1945. Then it downsized quickly. “By November 1945, it was pretty much a ghost town,” Cornelius says. “They kept a skeleton crew around until it was given to the Illinois National Guard in 1947.”

The Illinois National Guard didn’t stay for long and the land was considered for other purposes, such as an Air Force academy or an energy plant, but it was eventually decided to officially close the camp and sell the land back to local farmers.

While some farmers bought their farmland back for the amount they sold it, that wasn’t the case for everyone. Some of the land sold at market value since land value had gone up in the decade after it was originally purchased. Other land was auctioned off.

The problem – many were afraid to buy the land. “People were saying, ‘Why would you want to buy that land? The government is just going to come along in another 10 years and take it away from you,’” Cornelius says.

In the years after, the government didn’t take the land away again. The hospital, airport, living quarters and other buildings have all been torn down. In fact, there isn’t much left of Camp Ellis.

The two water towers remain on Rifle Range Road; one has been converted to store grain. Along the same road, the concrete walls of the rifle range, where target practice took place, still stand and are covered with layers of spray-painted graffiti from over the decades.

Viewed from the road, a lone chimney still stands long after its building was demolished. “After they took all the buildings away, if you would have gone out there then, there were probably thousands of chimneys out there,” Cornelius says.

The concrete dam built in the river by Bernadotte still exists. It was built to create a pool for a water supply, and the water was pumped up to the nearby concrete remains of the water filtration plant.

For the past 15 years, the Army Corps of Engineers have worked at the Camp Ellis site to remove leftover unexploded ordnance and pollution sites. This year, the sewage treatment plant, a large concrete structure that could be viewed from both sides of the road, was demolished because it was considered a polluted area.

“Camp Ellis was here and now it’s gone,” Cornelius says. “People who live in this area don’t want to forget Camp Ellis, but it’s easy to because there’s nothing left except for few concrete structures. Everything else is gone.”

The Camp Ellis exhibit in the Easley Pioneer Museum wasn’t originally planned. Dickson Mounds, the nearby state museum, had a temporary Camp Ellis exhibit and loaned it to the museum. The exhibit has grown since then. Cornelius says people will often come in to donate or lend artifacts to the museum to display.

“I’ve even met about 20 Camp Ellis alumni here,” he says. “Every one of them has a story.”

If you’re interested in learning more about Camp Ellis and other local history by visiting the museum, you’ll have to wait until April. The museum is open April 1 through Nov. 1 on Tuesdays and Fridays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.