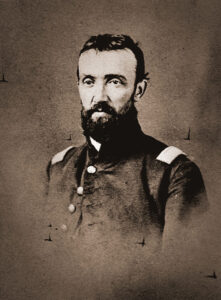

A lot of family trees have a fork connected in some way to the Civil War. My family tree’s connection was my great-great grandfather, Captain Deming Norton Lowrey and a disaster on the Mississippi River you’ve probably never heard about. The story includes some mystery, scandal and even some Illinois politics and wartime corruption.

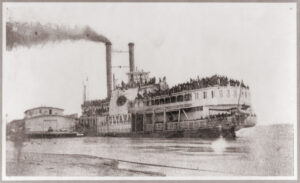

Capt. Lowrey didn’t die during the war. He died along with an estimated 1,800 other returning Union prisoners of war in the worst maritime disaster in American history, worse than the Titanic. You’ve probably never heard about the sinking of the SS Sultana, a side-wheel steamboat, on the Mississippi River because it happened at the very end of the war when prisoners were being exchanged. The war had hardened the public to the news of death and destruction. But mostly the disaster was overshadowed by one of the worst days in our nation’s history. It happened on April 27, just 12 days after President Lincoln died.

Capt. Lowrey didn’t die during the war. He died along with an estimated 1,800 other returning Union prisoners of war in the worst maritime disaster in American history, worse than the Titanic. You’ve probably never heard about the sinking of the SS Sultana, a side-wheel steamboat, on the Mississippi River because it happened at the very end of the war when prisoners were being exchanged. The war had hardened the public to the news of death and destruction. But mostly the disaster was overshadowed by one of the worst days in our nation’s history. It happened on April 27, just 12 days after President Lincoln died.

In fact the Sultana, a boat that regularly traveled from St. Louis to New Orleans, was tied up at Cairo, Ill. the morning of April 15, 1865 when news reached the city that President Lincoln had been assassinated. The captain of the Sultana, J. Cass Mason took an armload of Cairo newspapers with him and spread the news of the assassination as he travelled south, knowing the telegraph lines were almost totally cut off because of the war.

Reaching Vicksburg, Miss., Mason talked to Lt. Col. Reuben Hatch of Illinois, who was chief quartermaster for the Union Army at Vicksburg. This is where the tragedy of the Sultana starts. Colonel Hatch had a deal for Mason and it probably just required a little kickback.

Thousands of Union prisoners who had been held at the prison camps of Cahaba, near Selma, Ala. and Andersonville, south of Atlanta, Ga., had been shipped by train to a camp outside of Vicksburg awaiting release to the North. The U.S. government was ready to pay steamboat captains $5 for the transportation of each enlisted man and $10 for officers.

Colonel Hatch knew Mason and knew he needed the money. He said he could guarantee Mason a full load of 1,400 prisoners. Mason readily agreed to the deal.

The Sultana left Vicksburg and Mason continued to spread the news of Lincoln’s assassination on the way to New Orleans. On the way back up river to Vicksburg one of the four boilers on the Sultana sprang a leak that had to be repaired. But to do the job right it would have taken too much time and Mason would have lost his chance to take on the profitable human cargo. So instead a minor patch was made to the boiler.

Although the Sultana had a legal capacity of 376, it was packed with approximately 2,100 newly-released and half-starved prisoners of war, even more than Hatch had promised Mason. What was amazing is there were two other steamboats docked at Vicksburg that could have taken some of the soldiers north.

Although the Sultana had a legal capacity of 376, it was packed with approximately 2,100 newly-released and half-starved prisoners of war, even more than Hatch had promised Mason. What was amazing is there were two other steamboats docked at Vicksburg that could have taken some of the soldiers north.

With this large number of people the Sultana was totally overloaded and Mason worried about the boat being top heavy and listing from side to side. It is said he told one soldier that he would give all the interest he had in the boat if it safely landed in Cairo.

After three days traveling upstream and fighting the current of spring flooding that had widened the river to three miles, the Sultana’s boilers exploded. The cause was probably because of low water levels in the boilers and listing too far to one side causing the water levels to change drastically in the boilers. It was around 2:00 a.m. on April 27, 1865, just seven miles north of Memphis, Tenn., when the boilers exploded like a huge bomb tearing through the decks flinging men, wood, live coals and scalding water. The fire quickly spread and those who weren’t killed by the initial explosion had a choice of jumping into the icy water or being burned alive.

In the Civil War memoir of Harvey Hogue, who served with my great-great grandfather, he wrote, “It is said of Captain Lowrey that he remained on the sinking craft to the very last, throwing boards and such things as would be of use to those struggling in the water, when he might have saved himself by leaving earlier.”

Many of those who jumped into the icy water would drown or die of hypothermia. About 700 survived, but 200 of the survivors died later from their burns and exposure.

In spite of the huge disaster, and several inquiries, no one was really ever held accountable. Although there were several who it could be said reasonably shared in the blame, Col. Hatch seemed to have played a central role in the overcrowding that caused the listing of the boat, which in turn caused the unequal pressure in the boilers leading to the explosion.

In an episode of PBS’s History Detectives that aired on July 2, 2014, they found that Hatch had a long history of corruption and incompetence, but was able to keep his job and avoid court martial because of Illinois political connections back to Lincoln.

Earlier in the war while serving as an assistant quartermaster in Cairo, Hatch was arrested for taking kickbacks for the purchase of military supplies. The evidence was overwhelming. However, thanks to his brother Ozias Hatch, who was Secretary of State for Illinois and financial backer of Lincoln, plus the support of Illinois Governor Richard Yates and State Auditor Jesse Dubois, a letter from Lincoln to the judge advocate in Cairo spared Hatch from a court martial tribunal. His political connections would save his career several times, and even get him promoted.

After the sinking of the Sultana, Hatch was ordered to appear before another court martial tribunal. But, a request by the prosecutor to the Secretary of War for Hatch’s arrest went unanswered. Instead of having to answer to the charges, he was relieved of his duties as chief quartermaster. Weeks later he was carrying $14,490 in government money on a northbound steamer, the Atlantic. The safe on the Atlantic was robbed, but the thief was caught as the boat reached St. Louis. All but $8,500 of the government funds Hatch said he placed in the safe were recovered. Hatch’s career predictably ended in more scandal.

There isn’t a national monument to honor this forgotten tragedy. There is only a small monument in the Mount Olive Baptist Church Cemetery in Knoxville, Tenn., dedicated by the survivors in 1916.