“Be alert for any flu-like symptoms, aching joints, fatigue, rashes, bullseye rash, brain fog and so forth. If you experience any of these things, see a doctor … soon.”

“Be alert for any flu-like symptoms, aching joints, fatigue, rashes, bullseye rash, brain fog and so forth. If you experience any of these things, see a doctor … soon.”

That advice from Michigan resident Brian Anderson does not involve the illness you can’t escape hearing about all day, every day. Anderson has provided training for co-op and utility line crews in his home state and in Wisconsin, coaching them to avoid one of the more unpleasant possibilities arising from outdoor work in the woods and fields – Lyme disease.

The listed symptoms – especially a rash resembling a bullseye with a red center and two or more concentric rings – add up to a clear message. “DO NOT put off seeing a doctor,” Anderson emphasizes. “Early diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease is extremely important. If left untreated, it will only get worse, and after several months, it is really hard to get rid of.”

Delay exacts a painful price

Bert Lehman knows all about the importance of early treatment because, through no fault of his own, he didn’t get it. A dozen years ago, his case of Lyme disease went undiagnosed even after its effects were getting out of hand. Lehman began noticing numbness in his arms, legs and feet in July 2008.

He suspects he was bitten by a tick while doing outdoor photography earlier that summer. In June, he began suffering daily headaches. Within weeks, his symptoms grew to include backache, joint pain and muscle spasms. “I felt like my equilibrium was off,” Lehman says. “I felt unsteady; it was a foggy feeling.”

When the numbness appeared, he contacted a doctor and, with discomfort in his left arm, was dispatched to an emergency room to test for heart problems. He checked out okay and the mystery went unsolved.

Lehman then asked to be tested for Lyme disease and the result was negative. Later he learned testing at the time returned false negatives at rates as high as 50 percent. Nothing got better, and by fall 2008, Lehman persuaded his doctor to treat him for Lyme disease. Progress, if any, was slow, and the doctor halted antibiotic treatment. At one point, Lehman says a rheumatologist told him the problems were all in his head.

He found a website where he could enter his zip code and view a list of “Lyme-literate” physicians in his area. They were much in demand; his first choice was booked months in advance. In December, another doctor began antibiotic treatment. By March 2009, the physician he initially hoped to see put him on a course of three antibiotics, lasting more than a year and a half. Each bimonthly visit revealed progress against the Lyme symptoms.

All this time, work was a challenge. “I was lucky to have an office job because just walking would cause muscles to tighten up. I kept working and struggled through it,” he says.

A frontline facility

Wisconsin has become a hub for research into Lyme and other tick-borne illnesses, highlighted by the opening of the Tick-Borne Illness Center of Excellence, Woodruff, Wis., a combined research and treatment facility. The center is a project of the Woodruff-based Howard Young Foundation and the Open Medicine Institute, headquartered in California.

Dr. Andreas Kogelnik of the Open Medicine Institute, founding director of the center, says that tick-borne illnesses formerly more common in the northeast have been spreading southward and “exploded” in the past decade. Kogelnik says he considers it telling that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently increased estimates of active infections nationwide “by an order of magnitude from 30,000 cases to 300,000.”

Kogelnik acknowledges the difficulty of accurately diagnosing Lyme disease. “Testing is definitely a big problem,” he says, noting the false negatives and different types of tests. The center’s to-do list includes a cross-sectional study of the performance of various tests. He says right now “there isn’t a gold standard.”

Kogelnik says part of the trouble is that the wide-ranging symptoms vary. “If you have some selection from a list of several, it’s probably Lyme,” he says. The bullseye rash “is relatively specific but shows up in fewer than half the patients.” He notes, listing among other indicators “fever, cognitive neuropathy, just plain fatigue and joint pains that move around.”

It might be a stretch to say Lyme disease has been the direct cause of deaths, but it certainly has the capacity to trigger or aggravate other conditions that can be fatal, Kogelnik explains, noting a colleague died of a heart condition attributed to his Lyme disease.

Is Lyme disease fully curable with antibiotics?

“It’s realistic, but as with any infectious disease early treatment is better and the result depends on the underlying state of the patient’s immune system,” he says.

One hopeful note is the CDC says a tick must remain attached for 36-48 hours before Lyme disease bacteria is transmitted to the host. A close inspection immediately after visiting areas of likely exposure may afford ample time to remove the bug before infection occurs. “We have patients walk through our door every day with ticks on them, and we test the ticks as well as the humans,” Kogelnik says.

Don’t get bit!

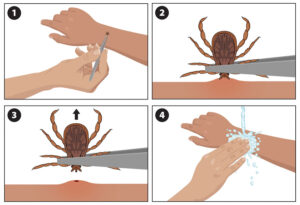

Brian Anderson says removal of an embedded tick is best accomplished gently. Using fine tip tweezers or a tick key, “grab it right down at the skin level and pull it straight up.” Squeezing the tick’s body is a bad idea, as this may inadvertently inject infectious material. With the tick removed, Anderson recommends cleaning the nearby skin with ordinary rubbing alcohol and retaining the tick in a plastic bag for potential testing.

Brian Anderson says removal of an embedded tick is best accomplished gently. Using fine tip tweezers or a tick key, “grab it right down at the skin level and pull it straight up.” Squeezing the tick’s body is a bad idea, as this may inadvertently inject infectious material. With the tick removed, Anderson recommends cleaning the nearby skin with ordinary rubbing alcohol and retaining the tick in a plastic bag for potential testing.

Desirable as quick diagnosis and treatment may be, a better option is preventing tick bites in the first place. “Walk on paths, stay away from tall grass and low vegetation,” Anderson advises, adding that “ticks need moisture for survival so they will tend to be more in shaded areas than sunny areas. They don’t fall from trees, they don’t jump, they just sit on a blade of grass or something until a host comes by, then hitch a ride and look for a meal.”

Light-colored clothing and tucking trousers into socks will aid in seeing the noxious creatures, and members of a group should watch for ticks hitchhiking on each other’s clothing when outdoors. Anderson runs a business as “The Tick Terminator” and mentions that those whose daily routine involves outdoor work can achieve effective prevention by treating shoes, clothing and gear with permethrin before venturing into likely tick habitat.

Light-colored clothing and tucking trousers into socks will aid in seeing the noxious creatures, and members of a group should watch for ticks hitchhiking on each other’s clothing when outdoors. Anderson runs a business as “The Tick Terminator” and mentions that those whose daily routine involves outdoor work can achieve effective prevention by treating shoes, clothing and gear with permethrin before venturing into likely tick habitat.

Long haul to recovery

Bert Lehman’s case took more than two years to fully resolve. He’s fine today but warns anyone spending much time outdoors to acquaint themselves with all the symptoms – he didn’t have the telltale bullseye rash. If symptoms appear, be sure to see a doctor familiar with Lyme disease.

“After this all took place, it was several years before I felt comfortable going into wooded areas or tall grass,” he says. Now, after he’s been in such areas, he showers and washes his clothing right away.

Even after decades of gradually growing awareness, Lehman says he’s concerned that Lyme disease is widely misunderstood. “The experience taught me that it’s not as simple as getting a bullseye rash and being on antibiotics for 21 days.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Electric Cooperative News.