Bill Arthur always knew there was a chance he had it. His father and two of his aunts did, and when Bill was 4 or 5, his father had a kidney transplant. It wasn’t until the age of 30, it was discovered he, like his father before, had polycystic kidney disease (PKD).

PKD is a genetic disease that causes clusters of cysts to develop within the kidneys, causing them to enlarge and lose function, leading to kidney failure.

After the diagnosis, Bill’s blood creatinine levels were followed to monitor his kidney function. He knew it was just a matter of time before he needed a kidney transplant.

He was referred to Barnes Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Mo. and Dr. Seth Goldberg. As the years passed, his kidney function continued to drop. Dr. Goldberg was closely monitoring it, because, if possible, he didn’t want Bill to have dialysis. The outcome for transplant patients is better if they can avoid it.

“Over the years, my kidney function just slowly got worse, and I was put on the transplant list in late 2015,” Bill says. “It usually takes two to five years to receive a match; it all depends on your blood type. The more uncommon the type, the harder it is to match.”

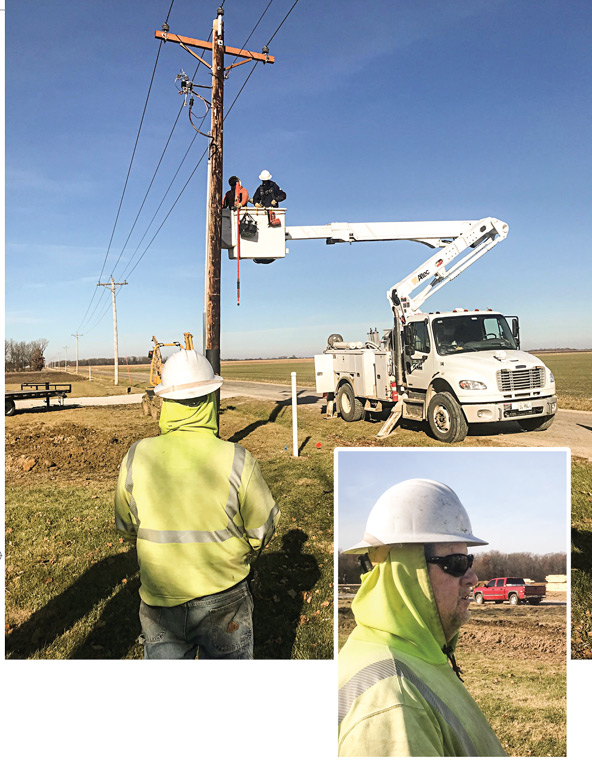

Bill is a line foreman at Coles-Moultrie Electric Cooperative in Mattoon. After hearing his story, one of his co-workers offered to give him one of his kidneys and went through all the testing. “He was a perfect match,” Bill explains. “It was like we were blood relatives, that’s how good of a match it was. However, when being tested, it was discovered that he had polyps on his lungs, and the doctors wanted to monitor those for a year to be sure it wasn’t cancer. It would have been a year this past October. If it was all good at that point, we would have done it.”

In the meantime, Bill continued to wait. He went through a full medical and psychological evaluation at Barnes Hospital and learned about transplants. “My wife Tonja and I talked to the hospital’s financial folks, and I met with a psychiatrist to talk about the process and how I was feeling about having a transplant. We went to several meetings and talked to some patients undergoing dialysis. We had to be prepared in case my kidney function got to the point where I needed dialysis while I waited,” he says.

“Tonja and I weighed all of the options for how I would get dialysis if needed and had a backup plan, just in case,” he says. “Our daughter was playing sports, and we traveled a lot to her games. I needed to be sure I could get it when I needed it. I also talked to Jim [Wallace], my boss at Coles-Moultrie, and with Kim [CEO Kim Leftwich], who told me to do what I needed to do. They were very supportive and willing to be flexible about my work schedule.”

Bill recalls the occasion when he received his first long-awaited call from the transplant team. “I got a call that I was the backup recipient. They always have a backup in case the primary recipient arrives and has a fever or some other medical issue and can’t have the surgery. We sat there for three days and then were sent home,” he says with frustration. The wait continued.

Meanwhile, his kidney function continued to deteriorate, and he was having a lot of pain in his legs.

His 50th birthday will be forever in his mind. “At 9 a.m., the day after my 50th birthday, the transplant team at Barnes called and told me I was the primary recipient. They wanted us to come right down. Well, the night before was our office Christmas party, and afterwards Tonja had thrown a surprise birthday party for me. When I arrived, people were buying me drinks. I’ve never been much of a drinker, but that night I had several. I was so sick when I got home! That was the first thing that went through my head when I got the call – that I’d had the drinks and it would make me ineligible for the transplant. But I guess getting sick rid my body of the alcohol because all of my tests came back fine.”

Bill was too nervous, so Tonja drove the two hours to the hospital. From the minute they checked in at 1 p.m., the transplant team took over. “It’s a well-oiled machine down there,” Tonja says. “I’m sure it’s hectic, but you don’t see it.”

They started doing bloodwork and other tests as soon as they arrived, and he learned he was definitely receiving the kidney. “I’d always heard you had to get to the hospital as quickly as possible after being called for a transplant,” he explains. “But I later learned a kidney can be hooked up to a machine to keep it operating. They need you there quickly for the testing to be sure you are a healthy candidate for the transplant. They want optimal conditions to give you the best chance.”

The operation only took around two hours, and the surgeon was pleased with the results. Surprisingly, in kidney transplants, the old kidneys aren’t usually removed. Instead, the new one is placed in the abdomen, where it is easier to connect to the blood vessels and bladder. It makes it easier to address any issues that might arise.

Four days later they were back home.

“Before leaving the hospital, the transplant coordinator told me, ‘You are on the transplant team now,’” Bill recalls. “And he wasn’t kidding! He said I had to do everything by the book. If I screwed up and didn’t take my medicines or stopped calling in my info, they would kick me off the team and find me a new doctor in another hospital somewhere. They wouldn’t take care of me any longer. That’s how serious they are about it!”

He returned home with a drainage tube to help remove the extra fluid his body had been retaining. “I lost 30 pounds of fluid,” he says. “My kidneys just couldn’t process it.”

A month later, Bill was back in the hospital. Due to his compromised immune system he picked up some kind of illness. He couldn’t stand up and was running a fever of 103. He was given intravenous antibiotics twice a day, in the morning and again in the evening. After a week, he was sent home and Tonja handled changing the IVs.

Tonja says she was nervous about doing the job. “I don’t do well with blood. I was a bit worried, but I actually did well, and it didn’t bother me.”

Bill recalls only one time that was concerning. “My IV stand wasn’t very tall. I got up to use the bathroom, and it started back-feeding blood back down the IV tube. That freaked out Tonja! I sat back down to see what would happen, and it all went back to normal,” he says matter-of-factly.

Multiple medications are now a necessity of life. He has a large card that keeps track of them. When first released, he had blood drawn twice a week by a home nurse who also checked his vital signs. The blood was sent to St. Louis, and Bill would call the transplant team with his blood pressure, heart rate, temperature and weight. Based on all of that, adjustments would be made to his medications. Bill currently takes nine pills in the morning and another three at night. All are anti-rejection or anti-viral medications. Some he will take for the rest of his life.

Tonja says that through it all, they just took one day at a time and lived life the best they could. “He could have been on dialysis, but he tried to take the best care of himself. You have to keep a positive attitude to deal with something like this.”

Bill’s donor was a young accident victim who died of head trauma. The young man donated everything he could, and it helped many people beyond Bill. Out of respect for the donor’s family, no contact was allowed for three months after the transplant. At that point, the kidney foundation allowed them to write a letter of appreciation, but they couldn’t give Bill’s name or where he lived. It is the donor family’s prerogative to write back. Bill and Tonja received a letter giving them a bit more information about the family and the young man.

“We learned his family had no idea he had signed up to be an organ donor, until his death,” says Tonja. “They never knew, but they honored his wish. We wrote them but haven’t heard back. We’d like to meet them, but we left it up to them to decide if that happens. So, we wait.”

In September, in honor of the young man, and in lieu of a medical alert bracelet, which Bill can’t wear on the job for safety reasons, he had a tattoo put on his right forearm. It has the medical sign with the words, Kidney Recipient, 12/17/17 and includes the young man’s name.

Are you a registered donor?

The young man who donated Bill’s kidney was part of the Illinois Organ/Tissue Donor Registry. In Illinois, the Secretary of State’s office maintains the registry for those wishing to donate. By becoming part of the registry, the wish to be a donor will be honored after death.

According to the Secretary of State’s office, beginning in January 2018, the program was expanded, allowing 16- and 17-year-olds to register for the organ/tissue donor registry when they receive their driver’s license. Secretary of State Jesse White encourages donors to discuss their choice with their parents.

“Our main priority is to save lives,” said White. “Thousands of Illinoisans are waiting for an organ. Those who are waiting are someone’s mother, father, son or daughter. This law is an important step in reducing the number of individuals on the waiting list.”

By joining the First Person Consent Organ/Tissue Donor Registry, 16- and 17-year-olds are giving consent to donate their organs and tissue at the time of their death with only the single limitation that the procurement organizations (Gift of Hope Organ & Tissue Network and Mid-America Transplant) must make a reasonable effort to contact a parent or guardian to ensure they approve of the donation. The parent or guardian will then have the opportunity to overturn the child’s decision. Once the 16- or 17-year-old turns 18, that decision would be considered legally binding without limitation.

“Approximately 4,700 people are on the waiting list in Illinois, and about 300 hundred people die each year waiting for an organ transplant,” said White. “One person can improve the quality of life for up to 25 people. Currently, 6.5 million Illinoisans are registered with the state’s registry.”

To register with the Secretary of State’s Organ/Tissue Donor Registry go to LifeGoesOn.com, call 1-800-210-2106, or visit a local Driver Services facility.