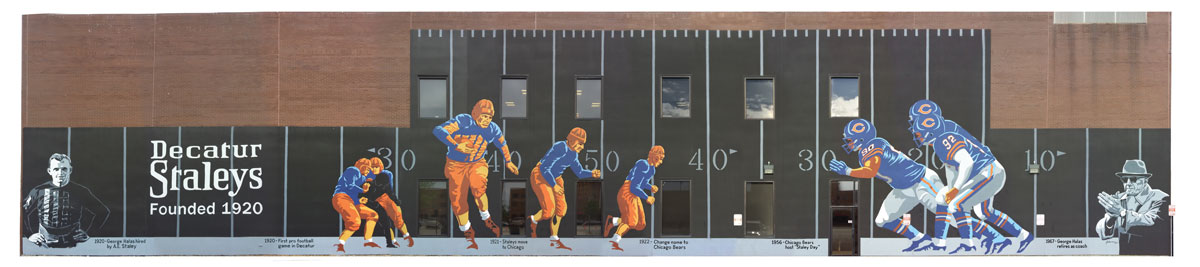

Nagurski, Halas, Payton, Sayers, Luckman, Butkus, Grange, Ditka – all recognizable names from a professional football team whose origin dates back a century to Decatur, Ill.

Even before there was professional football, there were industrial teams of factory workers, meat packers, steel workers and more—and that’s where the story begins.

A. E. Staley

Industrialist A. E. Staley came from humble beginnings on a small family farm in North Carolina and could be considered one of Decatur’s founding fathers, according to Laura Jahr, director of the Staley Museum in Decatur. “His contributions were wide, varied and important,” Jahr says. “One of his most important lasting marks was the pioneering in the field of soybeans, which is how Decatur became known as the soybean capital of the world.”

It was common in the early 1900s for companies to have clubs that provided a variety of entertainment for their employees. The Staley Fellowship Club was a club for employees and was responsible for their general well-being. It included anything from support for illness or death to promoting good entertainment.

“Staley wanted employees to be happy, because he knew that happy employees would come to work happily,” Jahr explains. “I think he also believed in an athletic program because he thought it would boost the qualities of good sportsmanship, character building and being a team player in the men and women who worked for him. It’s not clear whether it was his idea to have a football team or whether members of the fellowship came to him, but either way he thought it would be a good idea, and football was added to the program.”

In 1919, the Decatur Staleys, often called the Starchmen in reference to the company’s production of corn starch, were born.

Decatur Staleys

The evolution of the Staley football club to a professional team appears to date back to a game with the Arcola Independents. According to history, in their first meeting, the Staley team, consisting entirely of Staley employees, soundly defeated Arcola. The wounded spirits of Arcola businessmen spurred them to form a more competitive team before the next outing. They reached out to University of Illinois (U of I) running back Edward “Dutch” Sternaman and asked him to recruit a team from among the college ranks, which he did.

Staley caught wind of the plan, and his team didn’t show up for the game. He wouldn’t have them humiliated by a bunch of college players.

In turn, Staley reached out to Sternaman about helping him form a semi-professional football team. Sternaman, still finishing up his degree at the University of Illinois, wasn’t ready to commit. So, Staley turned his eyes to George Halas, a former U of I football player who was currently working for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad. Staley sent George Chamberlain, his general superintendent, to meet with Halas and make him an offer to work for Staley’s and coach and play football and baseball for the company.

Halas accepted the offer with a caveat. He would be allowed to recruit high-level players who would earn a regular salary by working at Staley Manufacturing Company and be given two hours a day to train with the team. They would also receive a part of the gate receipts at the end of the season.

According to Staley Museum sources, Halas took what some consider the “first professional football recruiting trip” and reported he had enlisted a team of players “that would draw standing-room-only” crowds. The first player he signed was former U of I teammate, Dutch Sternaman.

At the time, there was no governing body like the National Football League (NFL), and a wide variety of discrepancies existed due to the way teams were tallying which games counted as league games in terms of wins or losses, rules and regulations.

On Sept. 17, 1920, Halas and Staley engineer Morgan O’Brien met with a group of other team club members at an auto dealership in Canton, Ohio, to discuss possibly forming an association to adopt one set of rules which would govern all teams. The group sat on the running boards and fenders of cars on the showroom floor and worked out an agreement. The American Professional Football Association (APFA), which later became the NFL, elected well-known All-American football player and Olympic athlete Jim Thorpe as president. The Decatur Staleys became a charter member of the league.

Football practice started three days later

The sport was growing by leaps and bounds, but its growing popularity was causing problems. In its first year, the Decatur Staleys had a record of 10 victories, one loss and two ties and declared themselves league champions. However, the football field could only seat 1,500 fans with another 1,000 standing. Gate receipts weren’t enough to cover the cost of players, uniforms, equipment and travel. After the championship season, players wanted recognition in the form of increased salaries, but Staley was hard put to be able to meet their request because he was already paying them as Staley employees (a requirement to be on the team), and he couldn’t give them larger salaries than the other company employees.

Staley faced a conundrum. He had to decide whether he was going to own a football team or be a businessman.

“He had a lot of families depending on him,” says Jahr. “He was very empathetic with farming families, knowing personally how they can struggle. He was also gearing up for his soybean project, which started manufacturing soybeans in 1922. He had to make a choice, and he chose to follow the path of business. Football was entertainment, not a serious business for him.”

Staley met with George Halas and made him what some refer to as “an offer he couldn’t refuse.” Staley knew that big-time football needed big-city crowds, so it was agreed the team would move to Chicago and the players no longer had to work at the factory. In October 1921, a deal was made with the Chicago Cubs, which allowed the Staleys to play at Cubs Park, the predecessor to Wrigley Field.

The team moved with Staley’s blessing

In the March 1922 issue of The Staley Journal, it was announced that Staley Manufacturing was dropping its professional sports teams, both football and baseball. The announcement explained “…maintaining of teams has become so expensive that the company feels that it cannot continue to make up the big deficits each year. As long as the teams were composed of factory players the proposition served its purpose, but when the competition became keen for the high price players, the sport failed to serve its purpose for a business institution such as ours. Our directors have decided that we will confine our efforts to manufacturing, producing and marketing our products and that we cannot afford to continue in professional sports.”

Staley agreed to allow the 19 players to remain on the company payroll for one season and would give the team a $5,000 bonus, a considerable amount of money at that time, to help with the move. Halas agreed the team would play under the name of the Chicago Staleys for one season, after which they were free to change the name.

“The upside for Staley was the name recognition the company received that first year, which was a big marketing perk for him,” says Jahr. “I don’t think the team ever really forgot their historic roots here in Decatur, because, for many years, the players were many of the same ones that played here.”

At the end of the 1921-22 football season, the team name was changed to the Chicago Bears. Some believe the name was chosen because of the Cubs name, and others jokingly say it was because football players are bigger than baseball players.

Dutch Sternaman and George “Papa Bear” Halas became partners early in 1922, taking the team to Chicago and providing leadership. When a debate ensued over team ownership at a 1922 league meeting, the APFA contacted Staley. An agent was claiming ownership of the team. Staley told them the move to Chicago included Halas inheriting full ownership of the team, and the league voted in favor of Halas/Sternaman. Staley no longer owned the team but frequently attended games.

The Halas Era

In its inaugural season, the American Professional Football Association featured 14 teams, including the only founding members still in existence – the Chicago Bears and the Chicago Cardinals. The Cardinals moved to St. Louis in 1959 and to Arizona in 1988.

It was the Golden Age of football, and in 1925, Harold “Red” Grange, nicknamed “The Galloping Ghost,” arguably gave the league legitimacy. His popularity as a three-time All-American halfback at the U of I moved the Bears to sign him to a lucrative deal that included $3,000 per game and a percentage of gate receipts.

Prior to Grange joining the team, attendance at games averaged 7,500. At his pro debut, a standing-room-only crowd of 36,000 crammed into Cubs Park on a snowy Thanksgiving to witness a 0-0 tie with city rivals, the Chicago Cardinals. The Bears went on a 67-day barnstorming tour across the country, filling stadiums. They played 19 games in 67 days and drew crowds of more than 73,000 in New York and Los Angeles.

In 1929, Halas retired as player/coach and appointed Ralph Jones as his successor, but in 1933 Halas returned as coach and led the team to its first Western Division title and NFL Championship game.

Bronko Nagurski and Red Grange led the team in the 1930s, and the Bears were considered formidable. They played in the NFL Championship game four times and claimed the title twice.

During the late ’30s, Halas and Clark Shaughnessy, University of Chicago football coach, partnered on a new approach to the offense – the T-formation offense, which required a quarterback with quick decision-making skills. Halas recruited Sid Luckman to lead the offense, and the team became a high-powered scoring machine. The new offense confused opposing teams, but it was soon copied by pro and college teams alike.

The nickname “Monsters of the Midway” was first attributed to the Bears in the early ’40s after the team went to five championships and won four.

In 1942, Halas left for World War II along with 45 Bears players, leaving a lean team roster. In 1946, “Papa Bear” returned from the war, along with many other players, and the team was whole once again. It claimed another Western Division title and NFL Championship game. It would be the last championship game for 16 years.

The late ’40s to the early ’80s was a rough time for the Bears. The team put together good seasons but couldn’t finish when the division title was on the line. In 1955, Halas again left his coaching position but when the Bears dropped below .500 with a losing record, Halas once again took the helm.

In the first round of the 1965 draft, Halas drafted running back Gale Sayers from the University of Kansas and U of I defensive back Dick Butkus. Both had an immediate impact on the team and would become two of the best players in Bears history.

In 1967, the first NFL Super Bowl was played, and after 47 years, 72-year-old George Halas retired from coaching for the final time. He held a record 324 coaching wins, a mark that stood for almost three decades before being broken by Don Shula.

The popularity of professional football in the ’70s and the advent of the Super Bowl called for larger stadiums with at least 50,000 seats. The Bears left Wrigley Field after 50 years, and Soldier Field became their new home. However, the team floundered under a revolving door of coaches.

Running back Walter Payton was drafted in 1975 and would become one of the Bears’ greatest players. By the end of the ’70s, pieces were starting to fall into place for the team to make another run for the championship.

Early in 1982, Halas offered former Bears tight end Mike Ditka the head coaching position, and rebuilding began.

In spring 1983, George Halas succumbed to pancreatic cancer at the age of 88. “Papa Bear” was the last surviving NFL founder and the only person associated with the NFL throughout its first 50 years. He coached for 40 seasons and won six NFL titles. Halas’ eldest daughter, Virginia Halas McCaskey, and her husband Ed McCaskey were co-owners until his death in 2003.

The 1985 Bears season is the most celebrated year in its history. The pinnacle of the era was a Bears victory in Super Bowl XX. Behind quarterback Jim McMahon, the team had standouts Mike Singletary, Walter Payton, Dan Hampton, Richard Dent and William Perry.

Since Super Bowl XX, the Bears have had their ups and downs. In 1986 they won the NFC title and division title in 1988. The Ditka era came to an end in 1992 when the team finished 5-11.

The team struggled until 2007 when it won its first playoff game since 1994. Virginia Halas McCaskey accepted the NFC divisional George S. Halas Trophy (which had been renamed after her father in 1984) after the Bears beat the New Orleans Saints to win a trip to Super Bowl XLI. She called it “her happiest day so far.”

Virginia McCaskey is one of only a handful of female team owners. After the death of the Arizona Cardinals owner in October, she became the longest-tenured owner in the NFL.

Virginia and her family can often be seen watching the Bears play from the family box at Soldier Field.

For more information about A.E. Staley, his contributions to agriculture and the Decatur Staleys, visit staleymuseum.com.

For more information about A.E. Staley, his contributions to agriculture and the Decatur Staleys, visit staleymuseum.com.