“I can still remember in December 1937 exactly where I was and when I saw the lights come on. My brother and I were walking from the barn to the house and suddenly the house lit up and we were excited about that because it was the first time we had electricity in rural areas,” says Roy Goode. He became a power use advisor at Rural Electric Convenience Cooperative in Auburn in 1949 and eventually the co-op manager, launching his 42-year career there.

“I can still remember in December 1937 exactly where I was and when I saw the lights come on. My brother and I were walking from the barn to the house and suddenly the house lit up and we were excited about that because it was the first time we had electricity in rural areas,” says Roy Goode. He became a power use advisor at Rural Electric Convenience Cooperative in Auburn in 1949 and eventually the co-op manager, launching his 42-year career there.

Goode was excited just to see light bulbs burning in his family’s home 75 years ago. Fast forward to today. We flip a switch or press a button and expect to have light, heating, cooling, refrigeration and access to entertainment in our homes all because of electricity. We’ve become accustomed to having electricity that powers these conveniences and don’t even think about it until there is an outage. However, we should never forget our forefathers in the electric movement who believed rural dwellers deserved the same conveniences as those who lived in the cities and fought tooth and nail to bring electricity to rural Illinois.

Bringing power to the rural people

In the early-mid 1930s, 90 percent of urban dwellers had access to electricity, compared to just 10 percent of all rural residents. Private electric companies were convinced there wasn’t a decent profit to be made with just two to five farms and homes per mile. They also believed that no more than 10 percent of the people living in rural areas would be able to afford electricity and that farmers would not have the expertise to manage local electric companies.

That all began to change on May 11, 1935 when through the New Deal, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) as an agency within the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The executive order listed several duties and functions of the REA, and among them was, “To initiate, formulate, administer and supervise a program of approved projects with respect to the generation, transmission and distribution of electric energy in rural areas.”

This was the springboard for the modernization of rural America. Electricity meant progress. It was an arduous process, but the overwhelming desire to improve rural life was the driving force behind the program.

Goode was about 12 years old when the lights came on and clearly remembers what it took to start the process. “Immediately, the farmers and leaders in the communities had to work to sign up the members,” he said. “And at that time, the monthly membership fee in our area was $5, and the minimum payment was $3.25.” Goode said an immediate concern was that farmers weren’t accustomed to using cash every month. They were self-sufficient with their own chickens, milk and cows and didn’t need to spend money like we do today. This was going to be an uphill battle.

The co-ops had community meetings to educate the farmers about the benefits of electricity. But not everyone was convinced they needed electricity. Goode recalled, “One lady said she remembered that using candles and kerosene lamps made a good life. Then, after the power came on I talked to one farmer who said, ‘I believe it’s here to stay now and I guess I’ll sign up.”’

Larry Douglas, a retiree from the Southern Illinois Power Cooperative (SIPC) generating plant, a director of the Southern Illinois Electric Cooperative (SIEC) board of directors, and the son of K.R. Douglas, a pioneer on both the SIEC and SIPC boards of directors, remembers his father’s commitment to bringing electricity to their rural area. Larry recalls, “My dad was a leader in the co-op and was one of the people who actually got people to sign up for service. I think he even loaned some people money to buy their membership. Everybody had the same ideas and it was really a progressive bunch of people. But I’m sure there were people who said they didn’t want or need electricity. They had to overcome that and show them the benefits of it.”

K.R. Douglas and other leaders did whatever was necessary to move the initiative forward. Larry says his dad told stories about riding door to door on a mule signing people up for electric service. Back then, people who signed up for service at SIEC were given a rate book to read their meter and a pre-paid post card to mail in case of an outage. Today, many co-ops already know about an outage before the member even calls to report it.

Powering up southern Illinois

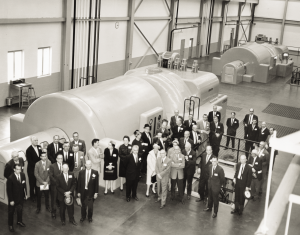

Southern Illinois Power Cooperative was organized in 1948 by distribution cooperatives SIEC in Dongola, SouthEastern Illinois Electric Cooperative in Eldorado, and Egyptian Electric Cooperative in Steeleville and a municipal provider, the City of Cairo. In 1959, as a 10-year bulk power agreement was ending, the three distribution cooperative members applied to the REA for a $25 million loan to build a power plant so they could produce their own electricity. The loan request was approved, and the group made history by acquiring the first REA loan for a generation entity.

K.R. Douglas was SIPC’s board treasurer when the loan was approved. “I remember him coming home one day and he’d gotten the first check for the money for the loan to build the plant. I don’t remember the exact figure, but he endorsed a multi-million dollar check to deposit for the project, and he about died,” says son Larry. He said the land to build the Lake of Egypt was purchased for considerably less than $100 per acre.

Many sacrifices were made along the way. During the construction of the power plant, K.R. Douglas quit farming for a couple of years so he’d have more time to attend meetings in Springfield and Washington D.C. “This was a big deal and of course they had to go to Washington D.C. multiple times to meet with government officials and REA people, and my dad was one of them,” says Larry. “I remember one time he came home and he’d been to John Kennedy’s office and the senator said he was going to run for president. Dad would tell people that, and they wouldn’t believe him.”

With the addition of distribution cooperatives Clinton County Electric Cooperative, Tri-County Electric Cooperative, Monroe County Electric Co-Operative and Clay Electric Cooperative, and numerous upgrades and construction projects, and various power supply agreements during the years since it was organized, SIPC is still going strong and remains a big factor in the area economy.

Building load and electric education

Roger Mohrman, retired manager and former power use advisor at Adams Electric Cooperative in Camp Point, remembers how the cooperative viewed members. “I always remember when I was hired, the fellow who was the board chairman made it real clear. He said you don’t work for us, you work for those members out there.” And Mohrman never forgot that. As a power use advisor in the early days, no grass grew under his feet. Mohrman says, “There were a lot of members who were just getting used to electricity and we made a lot of recommendations to solve wiring problems. And if a member had a complaint, we were usually the ones who went out and discussed it with them. I think it might have been as much public relations as it was about promoting electricity.” He went on to say that he promoted everything from light bulbs on up, but most importantly it was the combination of getting members to use more electricity while doing it more efficiently.

Annual meetings were also an effective way to promote uses of electricity, and Larry Douglas remembers them fondly. Southern Illinois Electric Cooperative’s Annual Meeting was a two-day event, which brought people in from five counties. The night before the meeting they’d have the queen contest, a talent competition and entertainment. Douglas recalls that it was always an August meeting and they’d put up the big tent and try to cool it down with giant fans. They’d have exhibits of conveniences that electricity could bring to the farm and home such as appliances and water pumps, which the co-op sold.

“When you look at what electricity did for agriculture, it’s phenomenal,” says Larry. “You have to remember that this was in the 1950s and they’d only had electricity for 10 years and they were so darned glad to have it. Electricity relieved people of the drudgery of housework and doing laundry and pumping water for the cows. Instead of having to crank up the gasoline engine, they could just flip a switch. And dairy farmers could use milking machines instead of having to do it by hand, and they now had refrigeration to keep it fresh.” Soon all these things helped the cooperative build their electric load.

Wrangling Mother Nature’s wrath

“Cooperation Among Cooperatives” is one of the seven cooperative principles, and an area where electric cooperatives really shine. Weather emergencies are always a challenge for electric providers, but with many more miles of line to maintain and repair during and after storms, rural cooperatives have their work cut out for them.

“The most challenging was the 1978 ice storm,” remembers Goode. “It was Good Friday when it started, and I thought this would be a regular ice storm. Before long, the phone rang and the answering service said the telephone was ringing so much they couldn’t keep up, and somebody needed to get to the office. I looked out and the trees were breaking, and I thought, oh boy here we go.”

During the height of the storm, in some cooperative territories, every member was without power. Some people compared it to a war zone. The devastation was massive. Power poles were snapped in two and tree branches and lines littered the ground everywhere. Goode says, “I went to the office and didn’t get back home for several days.”

During the storm, just like all Illinois electric cooperatives, Rural Electric Convenience Cooperative received assistance from the IEC Emergency Work Plan, which is administered by the Association of Illinois Electric Cooperatives in Springfield. When storms approach, association representatives contact cooperatives to request personnel, vehicles and equipment to help restore power to the affected cooperative territory or territories. It is why, even with more miles of line to maintain and repair, that cooperatives are among the first electric suppliers to have power restored to their members. Goode praises the AIEC for its assistance during that horrible ice storm, saying “We had crews in for that storm to help us all the way from West Virginia to Nebraska.”

Making a stand

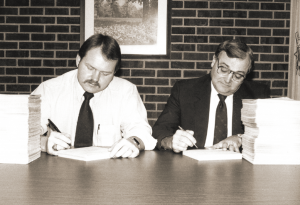

In the years since electricity came to the rural areas, co-ops have held their ground when it comes to legislative issues, and compromise has been crucial. In the early 1960s, territorial disputes were common, so cooperatives and investor-owned utilities worked together to draw up territorial maps, which led to the signing of the Electric Suppliers Act.

Mohrman says, “One issue that was handled very successfully after a long hard job was the territorial laws. Once they were in place, there wasn’t the continuous fighting over every individual who built a house. It was a long, hard fight, but for me at least, it was politically one of the most satisfying events I was a part of. It was a really big issue that turned out good, and they’re still using that basic plan yet today.”

Here to stay

Co-ops have always been resilient by adhering to the seven Cooperative Principles that guide the actions of all cooperatives. Mohrman says, “Co-ops are a good program, and there’s no problem too big that the group can’t solve if they work together.”

It’s the reason Larry Douglas joined the SIEC board. Douglas says, “It’s because of the knowledge I had about the co-ops and the fact that I could offer something. It’s something that’s been a big part of our family, and I just felt like I needed to be on the board. It is what’s made this country great—people out there doing things and getting involved and being willing to serve.”