As you drive through Illinois, it’s obvious from miles of green-ribboned fields that the state is a leading producer of corn and soybeans. But, you might be surprised to learn what other crops you might find in the state, and why they can be grown here.

Thousands of years ago, when the last glaciers moved across Illinois, they created the landscape we see today. In much of the state, they deposited the rich black loam conducive to growing those traditional crops. But in an area zig-zagging from western Cass County to the Indiana border, as far north as Woodford County and as far south as Piatt County, glaciers left behind sand that trapped water beneath the earth’s surface, forming the Mahomet aquifer. The ground covering the aquifer on one hand has a higher sand content perfect for growing certain specialty crops. On the other hand, much of the land would be useless without assistance from irrigation systems fed by the aquifer.

Menard Electric Cooperative, in Petersburg, serves 1,200 irrigation systems that pump water into wells from the Mahomet aquifer. Brady Smith, Menard’s engineering manager, explains, “The average main pump is just over 40 horsepower, and there are about 50,000 main pump-connected horsepower systems on the electric load. About 11 percent of kilowatt hours of electricity are sold through irrigation, comprising about 22 percent of our kilowatt demand.” And the irrigation load continues to grow by 30 to 40 systems each year.

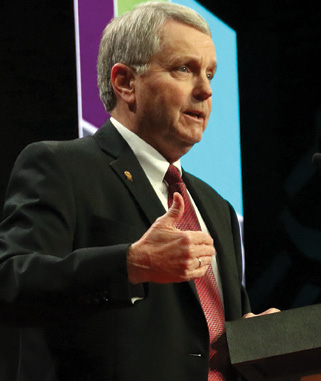

Former Menard Electric Cooperative Board Director Jerry Brooks, who farms near Oakford, operates 19 irrigation systems served by the co-op. Brooks says, “Where we’re standing near Oakford, we have about four feet of black dirt underfoot, then about 95 feet of sugar sand. Beneath that is limestone bedrock, but other areas don’t have the black dirt, and it couldn’t be farmed without irrigation.”

The unique soil blend, coupled with irrigation, enables farmers in the area to grow specialty crops such as green beans, sweet corn, melons, June peas, horseradish, gladiolas, barley, and potatoes for making potato chips. Traditional corn and soybeans can be grown there as well. Brooks says Libby’s and Del Monte count on area farmers for their pumpkin supply and other vegetables. Illinois is the highest producing state in the nation for horseradish and pumpkins. Mason County, located just a few miles north of Brooks’ farm, is the number one county in the country for popcorn and green bean production.

While these crops bring in good revenue, irrigating them is expensive. Brooks notes, “People drive by and see an irrigation system running on a growing crop. They don’t realize how much electricity, time and investment a farmer has to get water on it.”

A typical irrigator and water well can cost upwards of $100,000, and electricity for it can cost $40, or more, per day it operates. With so many moving parts, maintenance is an issue that is both time consuming and costly. “Some people call them irritators, instead of irrigators,” says Brooks. Ten electric motors operate independently, along with the water well. His irrigators collectively contain 250 tires that need to be regularly replaced, and miles of electric wire that can go bad.

Brooks explains that most irrigation systems are around one-quarter mile long. Initially, center pivot irrigation systems were water-powered, but today they are propelled by 480-volt electrical drive motors. Water is fed into a center pivot that rotates the sprinkler pipe in a circular fashion, supplying water to around 100 nozzles that spray the water. The pipe is supported by towers and moved along slowly in a circular path on wheels.

He details the science behind scheduling irrigation. “It takes three to four days to complete a circle with my typical irrigators. You look at your crop growing conditions, soil conditions, and the weather forecast. If it’s going to be hot and dry, or windy, or any combination of that creating low humidity, we tend to try to put water on before that event happens so that plant doesn’t suffer. You don’t want the plant to run out of water, or start conserving water. Professional ice hockey player Wayne Gretzky used to say that you skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it is now. Using that analogy, we try to apply water ahead of time and anticipate hot, dry conditions that could cause us to run short on water.”

There are ways to control irrigation costs. Menard Electric offers its irrigators a special interruptible electric rate to help avoid system peak electric use during summer when demand costs are the highest. The co-op can incrementally shut electricity off to the systems to avoid overloading the system and help keep rates down for all the co-op’s members. Smith says the co-op monitors the electric load through both its generation and transmission cooperative, Prairie Power, Inc., and Ameren, which owns the transmission lines over which the power must travel. He explains, “On a peak day, we try to get notifications out as early as we can to our members we’ll be controlling that day. We typically control four hours at a time.”

Technology is changing, and more irrigators are now able to enroll with vendors who have software that enables them to communicate with their irrigation systems using their smart phones, tablets, or computer. Smith says, “They’re able to start and stop the system, schedule when the system starts and stops, put down a certain amount of water at a certain time, and grab all their historical records of how much they pumped for the season, and when.” Menard Electric beta bested nearly 60 of its member systems utilizing the vendors’ software and communications with good results. It is currently studying to see if this method is a good solution for load control.

So, the next time you take a bite of pumpkin pie, enjoy your favorite brand of potato chips or gorge yourself on popcorn, remember that they could be on your table courtesy of irrigation from the Mahomet aquifer. For video segments of this story, please visit our website at icl.coop/irrigationinillinois/