Almost 1,000 years ago, the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site in Collinsville had a population of as many as 20,000 Native Americans. Today, the site is owned, managed and protected by the state of Illinois.

Cahokia Mounds is one of only 13 cultural locations in the U.S. designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a World Heritage Site. The designation officially recognizes Cahokia as a place of significant cultural heritage in world history. Additionally, it is a U.S. National Historic Landmark.

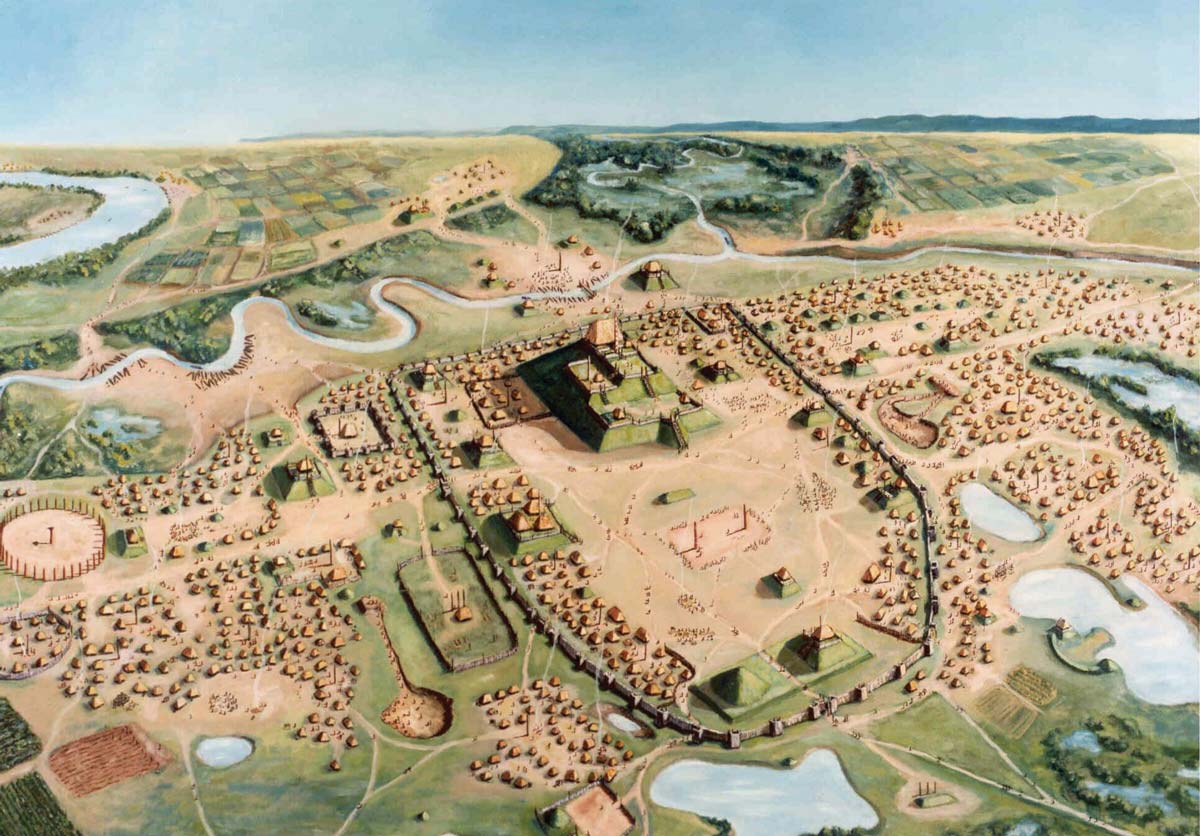

Referred to by historian and archaeologist William Iseminger as “America’s First City,” Cahokia site Superintendent Lori Belknap says that at its peak, the ancient metropolis encompassed over 4,000 acres covering six square miles.

“It is the largest pre-Columbian site north of Mexico,” Belknap says, adding that “it was occupied between 1050 to 1350 A.D.”

Known as the Mississippian Period, the era was characterized by the development of complex societies, agriculture and large-scale mound building and marks a distinct cultural shift from proceeding Woodland Period traditions in North America.

The Cahokia inhabitants, after whom the site was named, were members of the Illinois, a confederation of different tribes who were inhabiting the areas of present-day Illinois, Iowa and Missouri.

What distinguishes Cahokia are the 72 earthen mounds that remain within the site boundaries where the city once thrived. About 40 other mounds have been plowed over or lie outside the site boundaries.

Evidence suggests that dirt for the mounds was excavated from nearby borrow pits and carried in 40-pound baskets attached to a person by a strap worn over their forehead.

Dominating the Cahokia site is the rectangular Monks Mound, first referenced by frontiersmen in 1811 as a “stupendous pile of earth.” Built between 900 and 1200, it is the largest earthen structure in the Americas. Covering 14 acres at its base, it rises 100 feet. Measuring 955 feet in length and 755 feet in width, it is equivalent in size to the Great Pyramids of Egypt.

The current belief is that Monks Mound, as the central and most prominent structure in Cahokia, represented the power and organization of the city. It is thought it was the site of a large structure, likely used as a council house or an important meeting place, and possibly the residence of the Mississippian chief.

While there have been close to 100 separate archaeological excavation projects at Cahokia, less than 1% of the site has been studied by archaeologists.

Some of the most intriguing discoveries at Cahokia were uncovered between 1967 and 1971 during an excavation at what has been designated as Mound 72. Surprises began when a man’s torso was found buried on top of a carpet of 20,000 beads made from conch shells now known to have originated in the Gulf of Mexico.

Further digging yielded more insight into just how extensively the Cahokia inhabitants traded with other tribes. Two bushels of mica were uncovered and traced to the Smokey Mountains in North Carolina. Unearthed copper had origins around Lake Superior. Arrowheads found were made of stones from Oklahoma, Missouri, Wisconsin and Tennessee.

The story of Mound 72 did not stop there. The burial sites of about 300 people spanning hundreds of years were discovered in positions and alignments that led to a variety of interpretations of how and why their deaths occurred.

The treatment of some skeletal remains indicated they were of different social status. Several individuals had exotic goods buried with them as well as possible attendants whose bodies were buried alongside. The study of other remains revealed they had suffered violent deaths and had been tossed into a pit with little respect.

Another find at Cahokia is known as the Bird Man tablet, unearthed on Monks Mound. This mysterious sandstone tablet, only about 4 inches tall, shows a man wearing a bird-like mask or headdress, representing an eagle or peregrine falcon. The reverse side features a crosshatch design that may depict a snakeskin.

The symbolism is open to interpretation, and the figure has sparked much debate and speculation among archaeologists. Some believe the Bird Man may have held a significant spiritual or ceremonial role within the complex society of Cahokia. Others suggest a more practical function, such as representing a leader or warrior. Regardless of the meaning, the Bird Man remains a symbol of the ancient Mississippians and has been adopted as the official logo for Cahokia.

In the 1960s, archaeologists discovered the remains of a series of holes equally spaced in a circle. Studies revealed that posts had once filled the holes, forming a solar calendar that marked equinox and solstice sunrises and sunsets used for timing agricultural cycles and religious observances throughout the year.

Because of the similar use of the stone circles in England known as Stonehenge, Cahokia’s version of a solar calendar has become known as “Woodhenge.”

Today, the primary objective of site management is to preserve and respect the sacred history of Cahokia. Future excavations are not planned. “By its nature, archaeological excavation is destructive, so we are mindful about disturbing the ground,” Belknap says.

From the peak of its popularity in 1100, occupation dwindled over a period of 200 years. By 1400, the once-popular site was deserted, a departure that remains shrouded in mystery.

“It may have been due to crop failure, a prolonged drought, a failure in leadership, floods or a combination,” Belknap says. “It is known that near the end of inhabitation the remaining Native Americans were not using the entire site and had moved to a small area before leaving entirely.”

While the lack of a written language makes it impossible to know exactly what happened, evidence suggests the Native Americans living on the site joined tribes in the Midwest. Although none had mound-building traditions, their political and social structures, and the symbols in their imagery, demonstrate links to Cahokia.

Members of the Cahokia tribe, after whom the site is named, inhabited the site briefly and lived on Monks Mound from 1735-1752, before leaving as their ancestors had done.

Today, Cahokia is visited yearly by people from every state and 80 nations. In addition to local and international visitors, Native Americans are frequent guests.

“They consider Cahokia a sacred site and often mention they feel a spiritual connection to their ancestors. It can be quite emotional,” says Angela Cooper, a site services specialist tour guide. “We have made it known that they are welcome to perform ceremonies here if they desire. Sometimes they request to have a moment alone for quiet reflection.”

Belknap adds, “To stand on Monks Mound and realize how important the site was to Native Americans and visualize the effort it must have taken to build is profoundly moving.”

LET’S GO

30 Ramey St., Collinsville

Admission: free

Grounds open daily from dawn to dusk.

For more information, go to cahokiamounds.org.